|

Clinical Image

Sjogren’s syndrome presenting as plasma cell rich acute interstitial nephritis

1 DO, Department of Internal Medicine, Genesys Regional Medical Center, USA

2 MD, Department of Nephrology, Genesys Regional Medical Center, USA

3 MD, Department of Pathology, Genesys Regional Medical Center, USA

Address correspondence to:

Michael Beattie

D.O., Medical Education, Genesys Regional Medical Center, 1 Genesys Pkway Grand Blanc, MI 48439,

USA

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 100027Z11MB2018

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Beattie M, Kinning M, Mohammed A, Haus C. Sjogren’s syndrome presenting as plasma cell rich acute interstitial nephritis. J Case Rep Images Pathol 2019;5:100027Z11MB2018.ABSTRACT

No Abstract

Keywords: Acute interstitial nehpritis, Hemodialysis, Sjogren’s syndrome

Case Report

A 71-year-old Caucasian female presented with a 3-4 week history of generalized weakness, fatigue, and myalgias. She had visited her primary care physician shortly after symptoms began and was placed on augmentin for a suspected URI. Medical history is significant for rheumatoid arthritis diagnosed two years ago. She had been on hydroxychloroquine since the time of diagnosis, as well as diclofenac as needed for pain.

Her symptoms continued to worsen despite antibiotics and the patient ultimately returned to her PCP at which time blood work was performed. This revealed an elevated serum creatinine of > 4 mg/dL with a known baseline of 1 mg/dL. The patient was immediately sent in to the emergency department (ED) where laboratory test confirmed a serum creatinine of 4.87 mg/dL with a BUN of 92 mg/dL. Further review of patient’s home medications revealed she had recently been started on omeprazole for reflux. Her only other medications were hydrochlorothiazide and lisinopril for hypertension. Review of systems at this time revealed that patient had a rash that began one month prior and subsequently resolved, as well as complaints of mild dry mouth for the past 8 to 12 weeks.

While in the ED, the patient was given intravenous fluids and all home nephrotoxic medications were held. Initial physical examination revealed fluid overload with 1+ lower extremity pitting edema to the mid shin along with rales in the lung bases bilaterally. On neurologic evaluation, the patient was alert and oriented to person, place, and time, however did have some mild confusion with disorganized thought and asterixis.

Vitals on arrival to the ED were BP 105/68, HR 82, T 36.5, RR 16, 96% on room air. Initial chemistry panel was as Na 134 mmol/L (136–144 mmol/L), Potassium 4.1 mmol/L (3.6–5.1 mmol/L), Chloride 96 mmol/L (101- 111 mmol/L), Serum bicarbonate 18 mmol/L (22–32 mmol/L), BUN 92 mg/dL (8–26 mg/dL), Cr 4.87 mg/ dL (.44.1.00 mg/dL). Serum phosphorous was 7.5 mg/ dL (2.5–4.6 mg/dL). Aspartate Aminotransferase was 14 U/L (15–51 U/L), Alanine Aminotransferase 20 U/L (14– 54 U/L), Alkaline Phosphatase 96 U/L (35-104 U/L) and total Bilirubin 0.3 mg/dL (0.3–1.2 mg/dL). Creatinine phosphokinase was 22 IU/L (38–234 IU/L). Complete blood count showed WBC 8.5 K/cmm (4.5–11.0 K/cmm), Hemoglobin 9.1 K/cmm (11.0-16.2 K/cmm), hematocrit 27.2% (36–46%), platelets 317 K/cmm (140–440 K/ cmm). A urine alysis was obtained: pH 5.0 (5–8), 1+ protein (30 mg/dL), negative glucose, ketones, bilirubin, blood, and nitrites. Moderate Leukocyte Esterase (250 Leu/uL), 11–25 WBC’s, 3–5 RBC’s, 11–25 cyaline casts, and few squamous epithelial cells, transitional epithelial cells, bacteria, and mucous threads were noted.

A nephrology consultation was obtained. Urine output was monitored, and over the initial 12 hours the patient was found to be oliguric with less than 0.5 cc/kg/ hr of output. With the constellation of oliguria, uremic encephalopathy, and elevated serum creatinine, the patient was initiated on hemodialysis via a central venous temporary dialysis catheter.

Given her rheumatoid arthritis history, an autoimmune workup was also performed. Serum Antinuclear Antibodies (ANA) titers returned negative at < 1:40, as well as serum neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) at < 1:20, anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) antibodies were 8 AU/mL (10–19 AU/ mL). Quantitative Complement 3 (C3) and Complement 4 (C4) levels returned were 129 mg/dL (90–180 mg/ dL) and 29 mg/dL (10–40 mg/dL) respectively. A total complement level was also normal at 140 CAE (60–144 CAE). Urine protein electrophoresis (UPEP) pathology had returned negative for any monoclonal gammopathy. Serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) values was within normal limits. The decision was then made to proceed with renal biopsy.

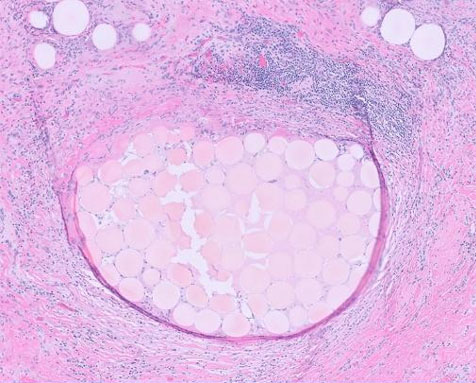

Histopathology revealed severe interstitial inflammation composed primarily of plasma cells with few scattered lymphocytes and eosinophils, with rare neutrophils. Moderate interstitial edema was noted with mild fibrosis and tubular atrophy (Figure 1). Mild intimal fibrosis of the arteries was seen as well. IgG4 immunoperoxidase stain showed few scattered plasma cell positive for cytoplasmic staining for IgG, kappa and lambda, with no evidence of light chain restriction.

Given the unique finding of plasma cell-rich acute interstitial nephritis along with the presenting symptomatology of generalized fatigue and weakness as well as several months of dry mouth, the diagnosis was made of Sjogren’s Syndrome. The patient was started on PO prednisone at 40mg daily. She received a total of two treatments of hemodialysis during her stay, and renal function rapidly improved. Her hyponatremia and metabolic acidosis resolved, and BUN and creatinine were 46 mg/dL and 1.71 mg/dL respectively at the time of discharge. She reported improved energy levels, as well as resolution of asterixis and confusion. She was discharged home with instructions to continue prednisone therapy with close follow-up with nephrology as well as rheumatology. Approximately 12 weeks after discharge, she was titrated down to prednisone 7.5 mg daily, and serum creatinine was back to within normal limits at 0.8 mg/dL.

Discussion

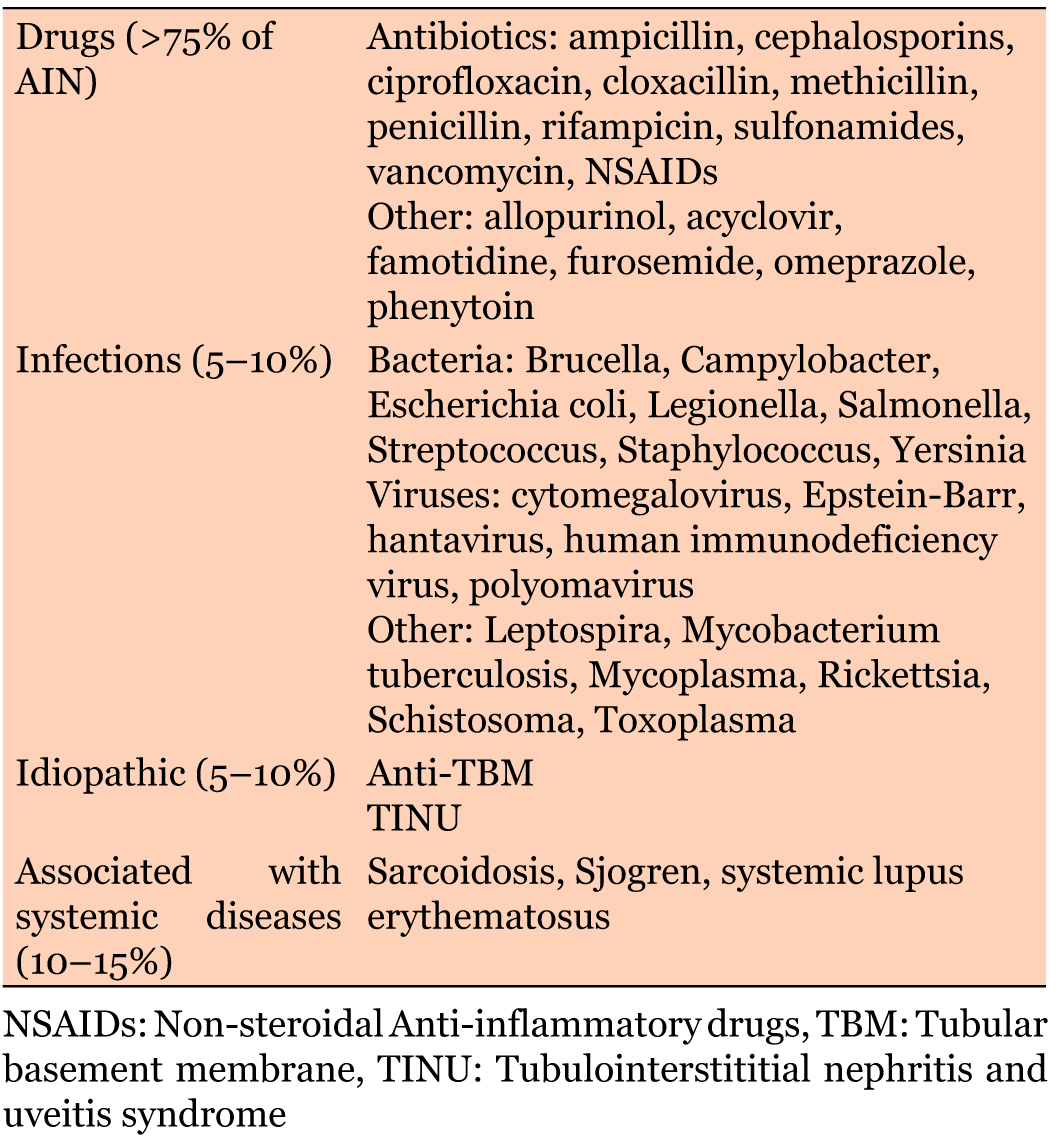

Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) is a relatively frequent cause of acute kidney injury. Studies have reported between 1–3% and 15–27% of all renal biopsies are diagnosed as AIN [1]. AIN can be divided into three major categories: drug-induced, infectious, and idiopathic. Idiopathic AIN includes tubulointerstitial nephritis (TIN), as well as other systemic diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjogren’s Syndrome (SS). More than 80% of AIN is thought to be secondary to either drug-induced or infection related causes, with more than two-thirds total being drug induced. Only about 10% of all AIN is related to systemic disease, including SS [1], (Table 1).

The classic presentation of AIN is typically nonspecific and may include symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and malaise [2]. Retrospective studies have demonstrated oliguria in approximately 50% of patients, and hematuria in 5% [1]. As mentioned above, drug-induced AIN is the most common subtype, and classically presents with a triad of rash, fever, and eosinophilia [3]. The symptomatology may also be linked to the underlying disease process, as in our patient who presented with associated xerostomia.

This patient was taking several possible offending medications including NSAIDs, PPI, as well as a recent course of antibiotics, all of which are more commonly associated with AIN. However, the key finding of plasma cell infiltration made SS the diagnosis. When AIN is seen in SS, pathology most commonly displays a T-lymphocyte predominance. Plasma cell infiltration, as seen in this patient, is rare. Only one other reported case was discovered in our literature search, and this case report was in a patient with a pre-existing diagnosis of SS [4]. When plasma cell infiltration is seen, multiple myeloma must also be considered. The lack of monoclonal gammomapthy on UPEP or SPEP for our patient made this diagnosis unlikely.

Sjogren’s syndrome (SS) is a chronic inflammatory disorder that is characterized primarily by lymphocytic infiltration in epithelial exocrine and extraglandular sites. When extraglandular infiltration occurs, it carries a significantly increased mortality. Retrospective studies have suggested approximately 4.3–5% of such patients that develop renal involvement [5]. When renal pathology does occur as a sequelae of SS, there are two distinct pathologic processes that can develop. The first is epithelial disease with a predominant mononuclear lymphocytic infiltration leading to tubulointerstitial nephritis (TIN), as seen in our patient. The second is an immune complex-mediated process resulting in glomerulopathy [5]. Of these two, TIN is more common. However, when interstitial nephritis is the presenting diagnostic finding of SS, it typically presents as a chronic interstitial nephritis rather than acute [4]. And as stated above, the infiltration is primarily T lymphocytes.

The typical SS symptoms of dry mouth and dry eye are typically present for a median of 5.5 years prior to manifestation of renal disease. This patient’s case is atypical as there was no pre-existing diagnosis or even suspicion of this disorder prior to hospitalization [6].

Other histologic findings that can be seen include tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis, both of which were identified in the pathology report. Typically, the elevation in creatinine is mild, however we observed an increase in creatinine of approximately five times the patient’s baseline that required hemodialysis [7].

The drastic elevation in serum creatinine along with the acuity of interstitial nephritis, plasma cell predominant infiltration, and lack of a diagnosis or suspicion of Sjogren’s disease prior to presentation is exceedingly atypical.

Conclusion

This case presents a rare etiology of acute interstitial nephritis requiring confirmatory pathologic diagnosis. It should serve as a reminder to keep autoimmune pathology on the differential for Acute interstitial nephritis.

REFERENCES

1.

Praga M, González E. Acute interstitial nephritis. Kidney Int 2010;77(11):956–61. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

2.

Kodner CM, Kudrimoti A. Diagnosis and management of acute interstitial nephritis. Am Fam Physician 2003;67(12):2527–34.

[Pubmed]

3.

Baldwin DS, Levine BB, McCluskey RT, Gallo GR. Renal failure and interstitial nephritis due to penicillin and methicillin. N Engl J Med 1968;279(23):1245–52. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

4.

Pijpe J, Vissink A, van der Wal JE, Kallenberg CGM. Interstitial nephritis with infiltration of IgG-kappa positive plasma cells in a patient with Sjögren's syndrome. Rheumatology 2004;43(1):108–10. [CrossRef]

5.

Evans R, Zdebik A, Ciurtin C, Walsh SB. Renal involvement in primary Sjögren's syndrome. Rheumatology 2015;64(9):1541–48. [CrossRef]

6.

Kidder D, Rutherford E, Kipgen D, Fleming S, Geddes C, Stewart GA. Kidney biopsy findings in primary Sjögren syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015;30(8):1363–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

7.

Maripuri S, Grande JP, Osborn TG, et al. Renal involvement in primary Sjögren's syndrome: A clinicopathologic study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4(9):1423–31. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Author Contributions

Michael Beattie - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Michael Kinning - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Drafting the work, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ali Mohammed - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Carolyn Haus - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guarantor of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2019 Michael Beattie et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.