|

Case Report

Ischemic cholecystitis masquerading as a metastatic disease secondary to transcatheter arterial chemoembolization

1 Batterjee Medical College, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

2 School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA

3 Division of Transplant Surgery at University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA

Address correspondence to:

Shareef Syed

505 Parnassus Avenue, #M884C, San Francisco, CA 94117,

USA

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 100087Z11SK2025

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Khan S, Arammash M, Syed S. Ischemic cholecystitis masquerading as a metastatic disease secondary to transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. J Case Rep Images Pathol 2025;11(1):18–21.ABSTRACT

Introduction: While difficult to diagnose, the accurate and timely identification of gallbladder metastasis secondary to hepatocellular carcinoma is necessary for appropriate patient care. Ischemic cholecystitis is a frequently documented complication of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) for hepatocellular carcinoma, which can resemble gallbladder metastasis.

Case Report: We present the case of a 53-year-old male patient with a history of compensated cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis C and right lobe hepatocellular carcinoma. The patient underwent partial hepatectomy of segment 5/6 and cholecystectomy post-TACE with intraoperative diagnosis suggesting possible gallbladder metastasis.

Conclusion: We describe the clinicopathological findings of ischemic cholecystitis masquerading as gallbladder metastasis and highlight the importance of perioperative histopathological finding to confirm the diagnosis and to differentiate the complications of TACE.

Keywords: Gallbladder metastasis, Ischemic cholecystitis, Transarterial chemoembolization

Introduction

Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) is a well-tolerated and widely used, targeted treatment for advanced liver tumors [1]. However, this procedure is associated with a risk of ischemic cholecystitis. The diagnosis of ischemic cholecystitis can be difficult given that it can sometimes mimic gallbladder metastasis, particularly in patients with a history of primary cancer treated with TACE with drug-eluting beads (DEB). The prevalence of post-TACE ischemic cholecystitis is between 0.3% and 10%. It is more prevalent in right lobar chemoembolization, likely due to the origin of the cystic artery from the right hepatic artery [1],[2], or radiation injury from the accumulation of 90Y particles [3]. Patients commonly experience abdominal pain accompanied by systemic symptoms such as fatigue, fever, and a group of symptoms referred to as post-embolization syndrome [4].

In a retrospective study, metastasis to the gallbladder was reported in 4.8% of all gallbladder malignancies [5]. Despite being rare, metastatic melanoma of the gallbladder, which is the most common form of metastatic disease of the gallbladder, can produce symptoms that masquerade as cholecystitis [6]. A poor prognosis was observed in patients who underwent acute cholecystitis cholecystectomy. Wakasugi et al. (2012) described a case of hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis to the gallbladder. During their hepatic resection, they performed a cholecystectomy to prevent postoperative cholecystitis. Despite not finding metastasis on the gallbladder macroscopically, pathological analysis confirmed the presence of tumor cells. Wakasugi et al. highlighted how difficult a preoperative diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma to the gallbladder can be, especially given the incidence being as low as 2.8%, and the importance of histopathologic analysis for confirmation [7].

Ischemic cholecystitis exhibits similar macroscopic intraoperative findings as metastasis with imaging findings not being reliable to differentiate in many cases. The differential should be investigated using a combination of multimodality imaging, CT findings of well-defined enhancing polypoid lesions with arterial enhancement and portal washout [8], laboratory parameters, histopathological examination, and patterns of gallbladder wall thickening [9].

Case Report

The patient was a 53-year-old male with a history of compensated cirrhosis secondary to chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, complicated by hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) localized to the right hepatic lobe. The patient’s surgical plan included a partial hepatectomy of segment 5, along with a cholecystectomy, following transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) for the treatment of HCC.

Preoperative planning involved a diagnostic mapping angiography procedure. Catheterization was achieved of the right hepatic artery, including the inferior pole branch of segments 6 and 7, as well as the superior branch of segment 8. No anatomical variants were identified. Embolization was subsequently conducted using Embozene drug-eluting beads (100 microns), with a total of one vial used for the procedure. Yttrium-90 (Y90) Theraspheres, with a prescribed activity of 9.5 GBq for segment 7 and 4.0 GBq for segment 6, were then administered. The targeted delivery achieved a 99% dose distribution.

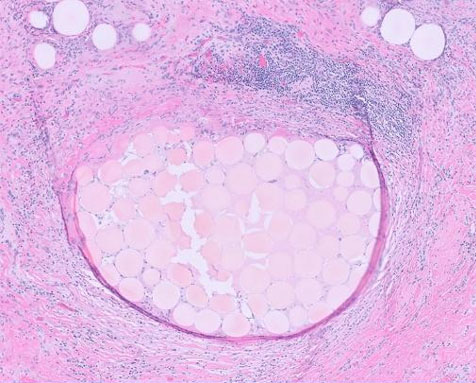

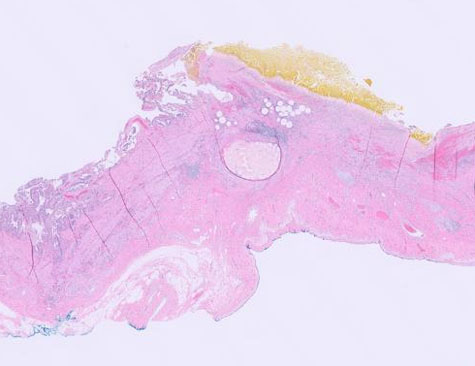

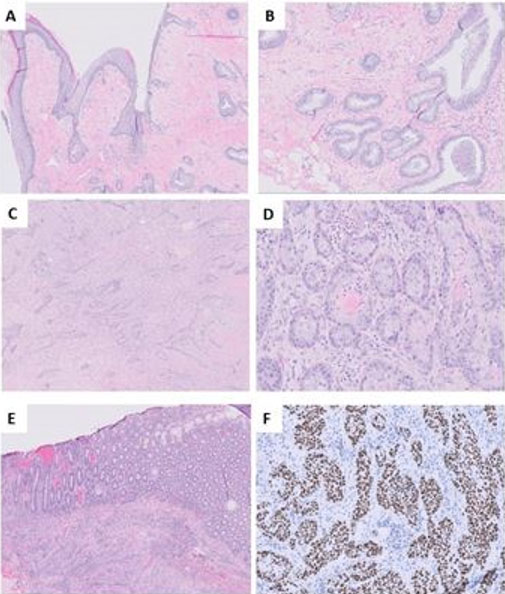

The patient had persistent disease identified on post-treatment imaging and was offered resection. Intraoperatively, the liver appeared to be cirrhotic with abdominal stigmata of portal hypertension. An abnormal appearance of the gallbladder infundibulum and neck was noted, a thick white appearance with a palpable mass. The gallbladder was resected and sent to the pathology unit for a frozen section to rule out metastatic disease. The palpable mass in the gallbladder which was noted to be consistent with a gall stone and the hard white area was consistent with chronic inflammation with embolic beads. Though there was suspicion of metastasis based on the gross appearance of the gallbladder, the final postoperative pathological diagnosis revealed cholelithiasis and chronic cholecystitis with chemoembolization beads with no carcinoma, as shown in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3.

Discussion

Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization is a commonly performed procedure used to treat patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) using drug-eluting beads (DEB) which reduce the vascular supply to the tumor. It is reported to have a 5% risk of major complications with a 1% risk of death. Major complications include hepatic failure, abscess formation, ischemic cholecystitis, pancreatitis, and pulmonary embolization [10].

Gallbladder ischemia after chemoembolization has been documented by various studies. According to the literature, the incidence ranges between 0.3% and 10% [11]. The risk of ischemic cholecystitis is elevated when the embolization beads escape into the proximal segment of the right hepatic artery or the proper hepatic artery or in a gallbladder where the cystic artery may originate from the left hepatic or superior mesenteric artery. Furthermore, the chemoembolization of lesions located in liver segments IV or V may also lead to an increased risk of cholecystitis [1], [12].

Ischemic cholecystitis’s clinical presentation can mimic that of other TACE complications, creating diagnostic challenges. Ultrasound and computed tomography (UT) imaging can be used to differentiate between cholecystitis and liver ischemia or pancreatitis. Additionally, in a case series of liver embolization, Chuang and Wallace [13] described that instances of right upper quadrant pain post-embolization could be particularly attributed to gallbladder ischemia, differentiating it from pain caused by liver ischemia or pancreatitis.

Differentiating ischemic cholecystitis and gallbladder metastasis is more difficult given the inconsistent imaging findings typically seen with cancer, but it carries significant clinical implications. Kim et al. found that while patients with gallbladder cancer typically showed focal enhanced wall thickening as opposed to diffuse in cholecystitis, irregular mural thickening and enhancement can be seen with cancer [8]. In patients diagnosed with gallbladder metastasis, widespread disease is commonly observed at the time of diagnosis and would warrant further oncological care such as chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy [14].

As seen in our case, it is important to confirm the intraoperative diagnosis by obtaining a frozen section of the gallbladder to analyze the histopathological findings and look for the waxy white gross appearance of ischemic cholecystitis with an absence of cancerous cells. This distinction is crucial to discern ischemic cholecystitis from direct extensions of malignancy or metastasis. Hence determining appropriateness of proceeding with liver resection.

Most studies documenting cholecystitis post-TACE, employed conservative management as the primary treatment approach. A study of ischemic complications after TACE by Tarazov et al. (2000) reported that ischemic cholecystitis could be successfully treated with percutaneous drainage and antibiotics [15]. It is crucial to emphasize the significance of cholecystectomy at the time of hepatectomy to minimize later complications and resolve patients’ symptoms effectively.

Conclusion

Differentiating gallbladder metastasis and ischemic cholecystitis can be difficult given the lack of reliable differences on imaging findings as well as macroscopic similarities. We describe a case of ischemic cholecystitis secondary to a TACE procedure that was intraoperatively suspected as gallbladder metastasis before pathological workup revealed the true diagnosis. This case highlights the importance of perioperative histopathological findings to confirm the diagnosis and to differentiate the complications of TACE. Accurate and timely diagnosis was essential to ensuring the patient received appropriate therapy.

REFERENCES

1.

Wagnetz U, Jaskolka J, Yang P, Jhaveri KS. Acute ischemic cholecystitis after transarterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma: Incidence and clinical outcome. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2010;34(3):348–53. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

2.

Karaman B, Battal B, Ören NC, Üstünsöz B, Ya?ci G. Acute ischemic cholecystitis after transarterial chemoembolization with drug-eluting beads. Clin Imaging 2012;36(6):861–4. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

3.

Singh P, Anil G. Yttrium-90 radioembolization of liver tumors: What do the images tell us? Cancer Imaging 2014;13(4):645–57. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

4.

5.

Yoon WJ, Yoon YB, Kim YJ, Ryu JK, Kim YT. Metastasis to the gallbladder: A single-center experience of 20 cases in South Korea. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15(38):4806–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

6.

Langley RG, Bailey EM, Sober AJ. Acute cholecystitis from metastatic melanoma to the gall-bladder in a patient with a low-risk melanoma. Br J Dermatol 1997;136(2):279–82.

[Pubmed]

7.

Wakasugi M, Ueshima S, Akamatsu H, et al. Gallbladder metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma: Report of a case and review of literature. Int J Surg Case Rep 2012;3(9):455–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

8.

Kim CG, Kim SH, Cho SH, Ryeom HK. Gallbladder metastasis of renal cell carcinoma: A case report. Taehan Yongsang Uihakhoe Chi 2021;82(4):959–63. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

9.

Gupta P, Marodia Y, Bansal A, et al. Imaging-based algorithmic approach to gallbladder wall thickening. World J Gastroenterol 2020;26(40):6163–81. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

10.

Clark TWI. Complications of hepatic chemoembolization. Semin Intervent Radiol 2006;23(2):119–25. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

11.

Wasser K, Giebel F, Fischbach R, Tesch H, Landwehr P. Transarterial chemoembolization of liver metastases of colorectal carcinoma using degradable starch microspheres (Spherex): Personal investigations and review of the literature. [Article in German]. Radiologe 2005;45(7):633–43. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

12.

Stefanini GF, Amorati P, Biselli M, et al. Efficacy of transarterial targeted treatments on survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. An Italian experience. Cancer 1995;75(10):2427–34. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

13.

Chuang VP, Wallace S. Hepatic artery embolization in the treatment of hepatic neoplasms. Radiology 1981;140(1):51–8. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

14.

Marone U, Caracò C, Losito S, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for melanoma metastatic to the gallbladder: Is it an adequate surgical procedure? Report of a case and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol 2007;5:141. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

15.

Tarazov PG, Polysalov VN, Prozorovskij KV, Grishchenkova IV, Rozengauz EV. Ischemic complications of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in liver malignancies. Acta Radiol 2000;41(2):156–60. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Author Contributions

Saleha Khan - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Mohammad Arammash - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Shareef Syed - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guarantor of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2025 Saleha Khan et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.