|

Case Report

Genetic insights of pediatric sudden cardiac death: A case report of anomalous left coronary artery originating from the right sinus of Valsalva

1 Department of Pathology at Texas Tech Health Sciences Center, El Paso, TX, USA

2 El Paso County Office of the Medical Examiner, El Paso, TX, USA

Address correspondence to:

Alejandro Partida Contreras

Department of Pathology at Texas Tech Health Sciences Center, 130 Rick Francis, MSB I Annex, Room 110, El Paso, TX,

USA

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 100094Z11AC2025

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Contreras AP, Rascon MA. Genetic insights of pediatric sudden cardiac death: A case report of anomalous left coronary artery originating from the right sinus of Valsalva. J Case Rep Images Pathol 2025;11(2):11–16.ABSTRACT

Introduction: Sudden cardiac death (SCD) in children is an uncommon but devastating occurrence. It is most often associated with congenital or acquired cardiac conditions such as cardiomyopathies, structural coronary anomalies, arrhythmias, and, less frequently, trauma-related events like commotio cordis. Coronary artery anomalies are identified in up to 10% of pediatric SCD cases and are usually detected at autopsy. Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery (LCA) from the right sinus of Valsalva (RSV) represents a particularly high-risk variant, especially during physical exertion.

Case Report: We describe a 15-year-old Hispanic male who collapsed during physical activity. He had no prior medical or family history, and no substance use. Autopsy revealed an anomalous LCA originating from the RSV. Next-generation sequencing identified a Likely Pathogenic SCN1A mutation and Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS) in LAMA4 and TRPM4, classified according to ACMG guidelines.

Conclusion: This case highlights the importance of comprehensive cardiac and genetic evaluation in pediatric sudden cardiac death. Morphologic assessment combined with molecular testing provides insights into the mechanisms of disease, improves risk stratification, and informs genetic counseling for at-risk family members.

Keywords: Cardiac death, Coronary artery anomalies, Forensic pathology, Sudden cardiac death

Introduction

Determining the true incidence of sudden cardiac death (SCD) in pediatric populations remains a complex task. Challenges arise from the difficulty in distinguishing between cases where cardiac arrest occurred independently and those in which it ultimately resulted in death—particularly in children, where most available data are obtained postmortem. The United States experiences sudden unexpected child deaths at a rate of 1.3 cases per 100,000 children annually. The death rate from cardiac disease accounts for approximately one-third of all pediatric sudden cardiac deaths. The three primary categories of pediatric sudden cardiac death (SCD) include structural heart defects and electrical system problems and acquired heart conditions. The most common structural heart condition that leads to pediatric sudden cardiac death is hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). The list of important causes includes hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) and congenital coronary artery anomalies and myocarditis and arrhythmogenic ventricular dysplasia [1]. The occurrence of congenital coronary artery abnormalities remains rare because they affect less than 0.24% to 1.3% of the total population. The right sinus of Valsalva (RSV) origin of the left coronary artery (LCA) stands out as a particular concern because it leads to sudden cardiac death in healthy young people. The left circumflex artery (LCX) has a more common occurrence when it originates from either the right sinus of Valsalva (RSV) or the right coronary artery (RCA). Other documented anomalies include a single coronary artery arising from the left sinus of Valsalva, both coronary arteries originating from the RSV, and cases where the left anterior descending (LAD) artery originates abnormally from the right sinus as well [2].

The etiopathogenic factors of some of these cardiac genetic abnormalities are not well understood despite advances in molecular medicine. Until now, the molecular pathways for the development of the coronary arteries have been clarified thanks to modern genetic techniques; nonetheless, the study of cardiac genetic aberrancies are still a work in progress [3] .

In this case report and accompanying literature review, we describe a patient who suffered sudden cardiac death and was found postmortem to have an anomalous origin of the LCA from the RSV, along with several genetic mutations.

Case Report

A 15-year-old Hispanic male with no previous medical, family, or social history complained of acute dyspnea and shortly after collapsed while exercising at school. Emergency medical services arrived at the scene, where essential life support was performed. The patient was transported to El Paso Children’s Hospital, where acute life support (ACLS) was performed; basic studies were conducted, including an electrocardiogram (EKG) with signs of ischemia (ST segment depression) and idioventricular rhythm (absent P waves and prolonged QRS segment]. The patient coded, and multiple rounds of CPR with electrical and chemical cardioversion were unsuccessful; at the time, the patient was pronounced dead at the hospital.

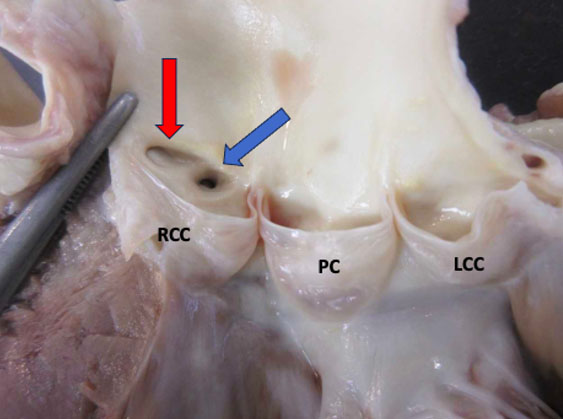

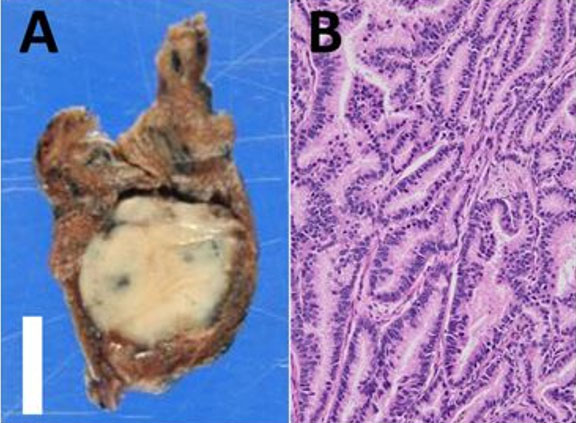

A postmortem examination was undertaken, and except for multiple small dermabrasions found at both knees, the external appearance of the body was unremarkable. The findings of the internal examination were also bland, except for the heart. The 253-gram heart had a standard size (decedent’s height of 67 inches and weight of 119 pounds). The epicardium was normal. The superior vena cava, inferior vena cava, and coronary sinus are connected normally to the right atrium. No thrombi were identified on the atrial appendage—unremarkable valves with normally formed leaflets. The right and left ventricles were well formed, composed of firm, brown myocardium with no gross lesions, and an average wall thickness of 3 mm for the right ventricle and 11–12 mm for the left ventricle. No signs of myocarditis or ventricular dysplasia were identified. The right coronary artery arose from the right sinus of Valsalva and followed a normal epicardial distribution between the right atrium and ventricle. The left coronary artery arose from the right sinus of Valsalva with an acute angle of the origin, the presence of a slit-like ostium, and an intramural course within the aortic wall, coursing between the main pulmonary artery and aorta (Figure 1). The foramen ovale was patent. The coronary arterial distribution was right dominant, with no atherosclerosis in the epicardial vessels.

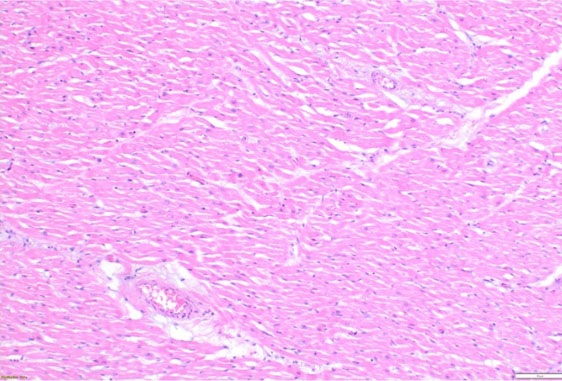

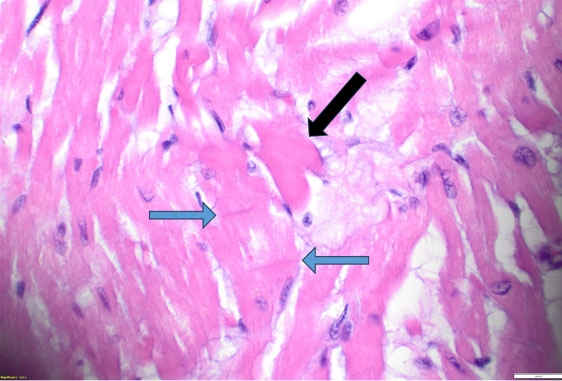

Histopathologic evaluation revealed scattered hypereosinophilic myocytes and contraction bands of the right and left ventricles (Figure 2 and Figure 3), consistent with global hypoperfusion, hypoxia, and catecholamine effect. No organisms were identified. No arteriosclerosis, fatty infiltration, dilated lymphatic vessels, or intercellular proteinaceous deposits existed.

Postmortem toxicology performed on femoral blood was positive for ketamine (940 ng/mL) and norketamine (48 ng/mL), which were used in the emergency room setting before his death. No common prescription drugs or illicit drugs were identified.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed for a comprehensive arrhythmia and cardiomyopathy panel with the following mutations:

- SCN1A gene, c.2353A>T (p.Met785Leu) variant.

- LAMA4 gene, c.4472G>A (p.Arg1491His) variant.

- TRPM4 gene, c.2531G>T (p.Gly844Val) variant.

One of the three mutated genes was deemed “Likely Pathogenic” (SCN1A), and the other two were considered “Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS)” (LAMA4 and TRPM4).

The cause of death was an Anomalous Origin of the Left Coronary Artery (LCA) from the right sinus of Valsalva, and the manner of death was certified as Natural.

Discussion

Anomalies of the left coronary artery (LCA) that originate from the right sinus of Valsalva (RSV) can occur in different anatomical forms such as inter-arterial (where the LCA passes between the aorta and pulmonary artery), intramural (embedded within the aortic wall), retroaortic (behind the aortic root), and anterior (coursing over the right ventricular outflow tract). The intramural path of the LCA through the aortic wall represents the highest risk for sudden cardiac death.

The precise mechanism of ischemia remains uncertain; however, the most commonly accepted explanation is that dilation of the aortic root during exertion compresses the intramural portion of the left coronary artery, thereby restricting blood flow through the LCA. The following factors may decrease coronary perfusion: a slit-like ostium, obstruction at the arterial origin, compression between the aorta and pulmonary artery, endothelial dysfunction, and coronary vasospasm. These anatomical and physiological characteristics both cause myocardial ischemia and increase the risk of sudden cardiac death [2] (Figure 1).

Clinical presentations vary widely. Approximately 20% of affected individuals experience exertional symptoms such as chest pain, dyspnea, or syncope. Sudden cardiac death is often the first manifestation of ALCA, and has been reported mortality rates range from 27% to nearly 100%. Some cases are discovered incidentally through imaging studies performed for unrelated findings, such as heart murmurs or abnormal electrocardiograms. Palpitations, dizziness, and presyncope symptoms often require echocardiography for further evaluation. These symptoms are not unique to coronary anomalies but commonly result in cardiology consultations and advanced imaging procedures. Stress testing combined with nuclear perfusion or echocardiographic imaging is used to evaluate ischemic risk primarily among athletes. Test results should be assessed with caution since normal results do not eliminate risk completely [3],[4].

Chromosomal abnormalities and specific genetic markers, including NKX2.5, GATA4, TBX1, TBX5, FOX1, Lefty, SMAD3, GDF1, HAND1, and HAND2, have been associated with several morphologic anomalies [5].

Kayalar [6] and others suggest that disruptions in the structural components of the aortic sinus cause abnormalities in coronary artery formation and positioning. Developmental imbalance in severe cases may block coronary artery formation so that a blind-ended pouch remains in the aortic sinus where the artery should originate. The research by Li et al. [7] demonstrated through mouse knockout experiments that the GJA1 gene functions as a critical factor for coronary development. The genetic variations found in our case have not been associated with coronary anomalies before but they could have acted as contributing factors to the multiple causes of death. The following section explains how each mutation influenced the heart functions of the patient.

SCN1A—Sodium Voltage-Gated Channel Alpha Subunit 1

The SCN1A gene produces the NaV1.1 sodium channel which enables sodium ion transport across excitable cell membranes to start neuronal signals and cardiac action potential transmission. Mutations of this gene can cause neurological and cardiac disorders that include epilepsy, autism spectrum disorders, arthrogryposis and unexpected fatal heart conditions without epilepsy [8]. The exact mechanisms through which SCN1A mutations result in cardiac death remain unknown but research indicates that these mutations affect heart repolarization and conduction by producing extended PR intervals and AV blocks and irregular heart rate patterns [9]. The fatal arrhythmia caused by mechanical compression of the anomalous LCA during physical exertion might have been worsened by the SCN1A variant, which was classified as “Likely Pathogenic” by ACMG and made the patient more prone to sudden cardiac death.

LAMA4—Laminin Alpha 4

The LAMA4 gene produces a laminin protein that functions to attach cells and guide their movement while sending signals through basement membranes. The particular function of LAMA4 in heart development remains unclear, even though researchers have established its role in embryonic growth and tissue structure [10]. The cardiovascular system of Lama4-deficient mice develops multiple defects, which include microvascular dilation with rupture as well as focal fibrosis and myocardial hemorrhage. The mice develop hypertrophic cardiomyopathy because of microvascular injuries while simultaneously showing abnormal endocardial cushion and atrioventricular valve formation. LAMA4 mutations found in humans result in hypoplastic left heart syndrome and infantile-onset dilated cardiomyopathy, together with severe forms of adult cardiomyopathy [11].

ACMG classified this LAMA4 variant as a Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS). The researchers performed gross examination yet found no evidence of the typical pathogenic LAMA4 mutation features, including coronary dilation, rupture, hemorrhage, and fibrosis. The microscopic evaluation revealed ischemia-related hypereosinophilic cardiomyocytes but no fatty myocardial replacement, characteristic of LAMA4-related disorders, thus creating doubt about the variant’s pathogenic effect.

TRPM4—Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily M Member 4

The TRPM4 gene functions as a calcium-activated ion channel that enables monovalent cation transport that promotes membrane depolarization. The cardiac electrical activity depends on intracellular calcium activation of TRPM4, even though it does not transport calcium directly. Through its regulatory functions, TRPM4 controls action potential formation in atrial tissue and pacemaker cell activity of the sinoatrial node, as well as Purkinje fiber conduction. The precise role of TRPM4 in ventricular myocardium remains poorly understood [12].

Research studies show that both activating and inactivating mutations of TRPM4 contribute to inherited cardiac arrhythmia syndromes and conduction disorders. Mutations that increase the membrane potential can render SCN1A sodium channels inactive while mutations that reduce the membrane potential decrease cell excitability. Experimental studies show that TRPM4 conduction function depends on environmental factors and protein–protein interactions [13].

According to Brugada et al. [14] TRPM4 directly correlates with SCN gene mutations, including SCN1A, which appeared in the patient. The researchers suggested that TRPM4-related alterations in resting membrane potential would disrupt NaV1 sodium channel functionality, most notably when the body experiences heat exposure which would lead to worsening conduction problems.

The patient’s fatal arrhythmia likely started when exertion and heat exposure caused ALCA compression that led to myocardial ischemia. The arrhythmia potentially became more severe because the patient carried the VUS TRPM4 variant together with the SCN1A mutation which likely increased the risk of sudden cardiac death.

Variant Interpretation and Broader Implications

Masson et al. [15] suggest replacing the ACMG terminology “pathogenic” and “likely pathogenic” with “predisposing” and “likely predisposing” because these terms provide better estimates of variant impact probabilities. The study shows how difficult it is to assess rare genetic variants while demonstrating why multiple factors, including allele prevalence and disease occurrence rates, and genetic diversity, must be assessed for variant classification.

Conclusion

Anomalous left coronary artery (ALCA) remains a hidden condition that makes it dangerous for sudden death. Complete autopsy procedures along with genetic testing, must be performed to better understand the exact cardiovascular causes behind these fatal cases because of the high death risk from untreated ALCA.

Undiagnosed congenital heart defects, together with cardiomyopathies and channelopathies in children, lead to sudden cardiac death (SCD). Morphologic evaluation of congenital abnormalities requires improved autopsy procedures, as some findings are only detectable at autopsy while others remain clinically silent. Postmortem examination of the heart reveals detectable congenital heart disease abnormalities, which investigative reports later show were present during previous clinical symptoms.

The determination of death causes in complicated pediatric cases requires detailed evaluation of coronary artery origins and paths, together with complete examination of heart valves, chambers, and septum. Molecular testing alongside these findings helps medical staff determine death mechanisms and establish the specific cause of death.

Molecular medicine continues to reveal how human heart morphogenesis depends on molecular pathways and how genetic abnormalities lead to autopsied heart anomalies. Further study is required to understand “gray areas” which include VUS because they stem from inadequate data and scarce patient information along with rare variants that correspond to disease-causing mutations. A Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS) generates clinical uncertainty which makes it difficult for healthcare providers and affected families. There are no established clinical guidelines for managing patients who receive these results so healthcare professionals must perform individualized interpretation.

Medical practitioners should not discard genetic variants because future genomic studies may classify them as “Likely Pathogenic” or “Pathogenic.” Genetic testing plays an essential role in both clinical and postmortem assessments to advance the understanding of these mutations. The approach will enhance variant classification while improving genomic databases, which will ultimately provide better guidance and reassurance for patients, their families and clinicians.

Better comprehension of infrequent coronary anomalies serves two purposes: it protects young individuals without heart disease history from unexpected death, and it directs cardiovascular genetics research and clinical practice. Healthcare providers use this knowledge to deliver genetic counseling for family risk assessment of patients, which leads to prevention of fatal cardiac episodes through early detection and proper management.

REFERENCES

1.

Scheller RL, Johnson L, Lorts A, Ryan TD. Sudden cardiac arrest in pediatrics. Pediatr Emerg Care 2016;32(9):630–6. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

2.

Khan MS, Idris O, Shah J, Sharma R, Singh H. Anomalous origin of left main coronary artery from the right sinus of Valsalva: A case series-based review. Cureus 2020;12(4):e7777. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

3.

Brothers JA, Frommelt MA, Jaquiss RDB, Myerburg RJ, Fraser CD Jr, Tweddell JS. Expert consensus guidelines: Anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017;153(6):1440–57. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

4.

Fragkouli K, Vougiouklakis T. Right coronary artery anomaly. Autops Case Rep 2021;11:e2020242. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

5.

Yasuhara J, Garg V. Genetics of congenital heart disease: A narrative review of recent advances and clinical implications. Transl Pediatr 2021;10(9):2366–86. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

6.

Kayalar N, Burkhart HM, Dearani JA, Cetta F, Schaff HV. Congenital coronary anomalies and surgical treatment. Congenit Heart Dis 2009;4(4):239–51. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

7.

Li WEI, Waldo K, Linask KL, Chen T, Wessels A, Parmacek MS, et al. An essential role for connexin43 gap junctions in mouse coronary artery development. Development 2002;129(8):2031–42. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

8.

National Center for Biotechnology Information. Gene: SCN1A [Homo sapiens (human)]. [Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene?Db=gene&Cmd =DetailsSearch&Term=6323]

9.

Ding J, Li X, Tian H, Wang L, Guo B, Wang Y, et al. SCN1A mutation-beyond dravet syndrome: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Front Neurol 2021;12:743726. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

10.

National Center for Biotechnology Information. Gene: LAMA4 [Homo sapiens (human)]. [Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene?Db=gene&C md=DetailsSearch&Term=3910]

11.

Boland E, Quondamatteo F, Van Agtmael T. The role of basement membranes in cardiac biology and disease. Biosci Rep 2021;41(8):BSR20204185. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

12.

National Center for Biotechnology Information. Gene: TRPM4 [Homo sapiens (human)]. [Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene?Db=gene&C md=DetailsSearch&Term=54795]

13.

Amarouch MY, El Hilaly J. Inherited cardiac arrhythmia syndromes: Focus on molecular mechanisms underlying TRPM4 channelopathies. Cardiovasc Ther 2020;2020:6615038. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

14.

Moras E, Gandhi K, Narasimhan B, Brugada R, Brugada J, Brugada P, et al. Genetic and molecular mechanisms in brugada syndrome. Cells 2023;12(13):1791. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

15.

Masson E, Zou WB, Génin E, Cooper DN, Le Gac G, Fichou Y, et al. Expanding ACMG variant classification guidelines into a general framework. Hum Genomics 2022;16(1):31. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Acknowledgments

We thank Emily Duncanson, M.D. at the Jesse E. Edwards Registry of Cardiovascular Disease in Minneapolis, MN, USA, for providing the cardiopathologic consultation and the gross examination image on this case.

Author ContributionsAlejandro Partida Contreras - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Mario A Rascon - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guarantor of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2025 Alejandro Partida Contreras et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.